My sister Darla and I had special little cups for our morning cocoa when we were very small. I think a lot of infants of my generation did in my home town of Wapakoneta. They were made of milk-glass and were engraved with decorations—my sister’s in red, mine in blue—that included little scenes of children sitting at a table and playing outdoors. Around the outer rim of each cup was the brief children’s prayer that we recited each time we were called upon to “say grace” before a meal: God is great/God is good/And we thank him for our food…

This was the only part of the prayer engraved on the cup, but when we said grace, we were required to recite the rest as well:

By His hand we shall be

fed/Give us Lord our daily bread/Amen.

We liked those tiny cups and

never tired of looking at the little scenes on them. They were comforting and

homey and made us feel somehow warm and protected.

But the same was not true of

the bed-time prayer we, and millions of other children, were required to learn:

Now I lay me down to sleep/I pray the Lord my soul to keep/If I should die

before I wake/I pray the Lord my soul to take/Amen.

This was a frightening enough

image that if you were a worrier as I always was as a child, it was hard to go

to sleep if those words kept resounding in your head. In fact, it was because

of that prayer that the thought dawned on me for the first time that adults

weren’t the only people who died. Kids could die as well.

I recall a trip to the cemetery

with my mother and my grandmother when they would engage in that strangest of

all smalltown pastimes: visiting the family dead. As we picked our wending way

through the myriad tombstones and monuments, we happened on several with

child-like images—granite markers topped with delicate child angels, Jesus with

tiny tots on his knees, a child’s statue with smiling face and arms thrown

tight around a beloved dog’s neck. Clearly these were different from the other

solemn stones.

I asked my mother about these

child-images, and she told me that they were the graves of little kids whose

souls were now in Heaven with Jesus. She smiled, admittedly a bit sadly, as she

said it, and the thought seemed to be that even though these precious little

tykes were dead, they were actually quite lucky because now they were in

Heaven, a much better place than Earth, at least for good little Christians.

But the cost-benefit didn’t

seem all that clear to me. And it appeared, furthermore, to be an absolute

crapshoot. If the Lord decided “your soul to take,” while you lay asleep, your

goose was basically cooked, because it would simply be the will of God, and

there was apparently no arguing with that.

The idea plagued me. From the

outset in my life, words mattered. I was sensitive to them and when the scary

words entered my head, there was no erasing them.

I was at least lucky not to

have been subjected to a similarly worded lullaby that some English-speaking

children in the world were given to think about at bedtime, if their mothers

happened to have a musical bent: If you

die before you wake/Do not cry and do not ache/Nothing’s ever yours to keep/So

close your eyes and go to sleep. How any even remotely sensitive child was

expected to get to sleep after having those almost accursed words sung to them

is really hard to say.

As if these lugubrious prayers

and lyrics weren’t enough to scare the bejesus out of us, we were also treated

to the macabre scenes served up by long-traditional nursery rhymes and

children’s verses. I suppose many kids who heard these read to them again and

again mainly just liked their iambic bounce and learned them by rote without

paying any great attention to the words. But words in my mind always formed

immediate and searing images, and the images that many of these traditional

verses conjured up weren’t, to say the least, pretty.

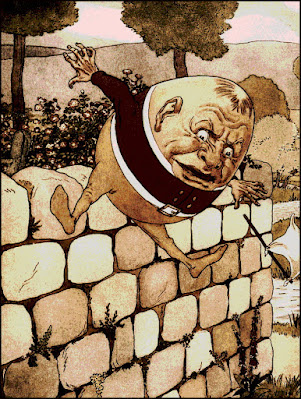

For instance: Humpty

Dumpty sat on a wall/Humpty Dumpty had a great fall/All the King’s Horses and

all the King’s men/Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

I was aided in imagining this

tragic scene by vintage storybook illustrations. A large top-heavy-egg-shaped

humanoid, dressed like a boy falls from a high wall and, it seems, shatters,

making such a mess of himself that he can’t be mended.

I would come to find out many

years later that, although our mothers, and their mothers, and their mother’s

mothers would mindlessly read these rhymes to us as if they were truly meant

for children—most of them could have done with at least a PG rating—they had,

in most cases, originally been clever verses comprising codes for the lower

classes that told stories involving those in power, and whose absolutist rule

precluded open criticism.

The story of poor Humpty, for

instance, dates back to 1648, a time of civil war in England. Humpty was

actually not a person, but an extra-powerful cannon that Royalist defenders had

mounted on a high tower-like wall next to St. Mary’s Church, above the

strategic town of Colchester. It was a vantage point from which royal

artillerymen could do some real mischief by firing directly down on Parliamentarian

forces seeking to take the town—where, truth be told, the absolutist monarchy

no longer was at all popular.

Parliamentarians eventually

rolled in all of the firepower they could muster and hammered the wall,

particularly its artillery emplacement, with withering cannon and mortar fire,

until they finally were able to bring both wall and cannon tumbling down. In

the end, “all the king’s horses and all the king’s men” couldn’t piece that big

gun back together again and hoist it back up onto the wall. The town fell to

the Parliamentarians, who took the “officers and gentlemen” prisoner, and set

the common soldiers free to return to their homes once they had sworn an oath

never to take up arms against the Parliament again.

Another rather disturbingly

nonsensical rhyme, Ring Around the Rosie,

is from just a bit later than Humpty in the seventeenth century, and is even

more tetric than it may sound: Ring around the Rosie/A pocketful of

posies/“Ashes, Ashes”/We all fall down!

It was less than two decades

after the English Civil War that London was gripped for about a year by The

Great Plague, otherwise known as bubonic plague. Despite its place of

historical significance—it’s hard to find a world history course that doesn’t

include it—The Great Plague is estimated to have killed about seventy-five

thousand people. In our times of yet another great pandemic, most American

politicians would consider “so few” plague fatalities to be a positive trend,

considering that COVID has killed more than a million Americans, despite the

early discovery of some of the most effective vaccines in history. But in all

fairness, the entire population of London at that time was probably not more

than four hundred thousand, so seventy-five thousand would have been about

eighteen percent of the total.

Anyway, the Ring Around The Rosie verse that we were

taught to sing in kindergarten as a cheerful little ditty—performed while

standing in a circle, holding hands, turning like a human merry-go-round, and

“all falling down” at the end of the last line—was actually all about the

bubonic plague. Symptoms of the dread disease included the formation of a bright

rosy-red-ringed rash on the skin of the victim. Although the infectious

illness—also known as the black plague—was caused by a bacterium prevalent in

rats and transmitted to the fleas that bit the rats and then bit people, many

Londoners at the time associated the disease with bad odors. They carried

flowers and herbs (posies) in their pockets to ward off the plague. And

finally, the bodies of the mounting dead (all those who had “fallen down”) were

incinerated.

What a delightful little rhyme! Don’t you think?

Another lovely illustration in one of the storybooks my mother read to us when we were small is of “Mistress Mary” the “contrary” little girl with her rake and watering can, tending the flowers in her perfect garden. This one didn’t seem scary at all, but it was indeed enigmatic. Mary, Mary quite contrary/How does your garden grow?/With silver bells and cockle shells/And pretty maids all in a row. The adjective “contrary” made me think of some snooty Little Miss Perfect who was only interested in her impeccable garden and would never think of playing with another child. But the most unfathomable part of that verse was the last line. Who were those “pretty maids” and why were they all in a row? Were they the flowers in Mary’s garden, the blooms of which might look a bit like the pretty faces of young women standing side by side?

Turns out, nothing so innocent.

Seems the Mary in the sixteenth-century rhyme was none other than Queen Mary I

of England. The eldest daughter and eldest child of King Henry VIII and his first

wife, Catherine of Aragon, she was passed over for queen in deference to her

half-brother Edward VI, Henry’s first and only son (this time with Queen Consort

Lady Jane Seymour, whom he married after having his second wife, Anne Boleyn beheaded).

Edward was the first British monarch to be brought up a Protestant after his

father broke with the Roman Catholic Church, which refused to grant him a

divorce from Mary’s mother, Catherine.

The almost inadvertent

religious reformation that gave birth to the Church of England—a basically

Catholic religion but with the British monarch as its head—was jealously

defended and expanded during Edward the Protestant king’s reign, in which he

was assisted by a royal regency, since he was only nine when he succeeded Henry

to the throne and fifteen when he died, probably of tuberculosis. Fearing that Mary,

a staunch Roman Catholic like her mother, might succeed her stepbrother and reverse

the Anglican reform, King Edward’s handlers helped him, during his long

illness, to devise an exception to direct succession and had him name his

cousin, Lady Jane Grey to assume the throne upon his death. But Mary wasn’t

having any of this and managed to have the new queen executed when Lady Jane

had only been sitting on the throne for nine days.

|

| "Bloody Mary" |

Even older than Mistress Mary

is the verse contained in the children’s song Baa, Baa, Black Sheep. We

sang that tune in kindergarten and first grade, and it seemed to encompass such

a sweet and pastoral image: Baa, baa, black sheep/Have you any wool?/Yes

sir, yes sir, three bags full!/One for the master, one for the dame/And one for

the little boy who lives down the lane.

But there was nothing really

sweet originally about this image. It was a satirical reference to the

consequences of a cruel tax imposed on the peasants in 1275, under the reign of

King Edward I. And it seems too, that the cheery last line that we sang was

reformed for later audiences, because the original words to that final line

went: And none for the little boy who cries in the lane.

In Medieval England, wool was a

major source of commerce and wealth. This was also the time of the Crusades,

and Edward I was in dire need of extra revenue to finance his armies, over and

above what he was already bleeding from his vassals, and so too, their serfs. The

rhyme, then, signifies that with still another tax being applied to the already

heavily taxed wool trade, a bag of wool would go to the king (the master) and his

landholding vassals, another to the Church (the dame), and nothing would be

leftover for the young shepherds (the little boy who cries in the lane), who

actually did the hard work of caring for the flock.

A few of the nursery rhymes we

kids in the US recited, however, were actually home grown. For instance: Rock-a-bye,

baby/In the tree top/When the wind blows/The cradle will rock/When the bough

breaks/The cradle will fall/And down will come baby/Cradle and all.

This strangely disturbing verse

dates back to the time of the Pilgrims. The arriving immigrants were fascinated

by a custom of the Native American women, who, it seems, took advantage of the

wind to rock their babies to sleep. They would do this by tying a makeshift

cradle between two branches with their crying baby in it, and allow the rocking

motion of the breeze to gently lull their child to sleep.

Some of the Pilgrim settlers found this disturbing. What happened, they wondered, if the weight of the cradle and child swinging from a tree was sufficient to snap a branch in two? Didn’t these women see how dangerous it could be?

Hmm, white people…always

stressin’!

Another American addition to

the nursery rhyme repertoire is, already on first glance, quite obviously

politically incorrect: Peter, Peter, pumpkin-eater/Had a wife and couldn’t

keep her/He put her in a pumpkin shell/ And there he kept her very well.

The meaning seems pretty clear.

It is a deadly if iambic warning to young women to not even think about

infidelity. Peter’s wife liked a little something on the side, and just look

what happened to her! He killed her and hid her body in a giant pumpkin

shell. End of problem.

Okay, obviously no women’s lib

or MeToo back then.

A much more modern nursery

rhyme that is utterly terrifying is the haunting and most famous (infamous?)

poem penned by Hugh Mearns (1905-1965), a dark if lilting verse entitled Antigonish. Besides being a poet, Mearns

was also a Harvard-educated pedagogy professor at the University of

Pennsylvania. The thrust of his research focused on stimulating creativity in

children ages three to eight. He joined, rather like a fly on the wall, the

conversations of kids in this age group and recorded his findings for later

application to his pedagogical studies.

Those who knew Professor Mearns

observed that when he was with children, he tried his best to fade into the

background and get them to forget there was an adult in the room. He never

asked the kids questions or showed surprise at any of the crazy things they extemporaneously

did or said. He merely observed and later typed up what he had seen and heard

in his notes.

What Mearns observed in kids

that prompted him to write Antigonish is hard to say, but whatever it

was, this particular “children’s verse” is singularly chilling:

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn't there

He wasn't there again today

I wish, I wish he'd go away...

When I

came home last night at three

The man was waiting there for me

But when I looked around the hall

I couldn't see him there at all!

Go away, go away, don't you come back any more!

Go away, go away, and please don't slam the door... (slam!)

Last

night I saw upon the stair

A little man who wasn't there

He wasn't there again today

Oh, how I wish he'd go away...

I can remember that in the huge

vintage house where we lived on West Auglaize Street, old Wapakoneta’s most

traditional and iconic residential street, the downstairs connected to the

three bedrooms upstairs solely by means of a windowless, narrow staircase that

was only accessible through a dark back corner of the kitchen. My parents slept

in the master bedroom downstairs, while my sister, brother and I slept

upstairs. I had no fear of that staircase during daylight hours, but when I had

to mount its steps alone at night for bed, there was always an instinctive terror

that something or someone awful lay waiting for me there in the darkness.

This image combined nicely with

the demented axe murderer/strangler/slasher who, my older sister had informed

me, might be waiting beneath my bed, just to grab me by the ankles and jerk me

under. So the route to bed was always a mad race up the steps and into my room.

Once there, I would leap from a safe distance into my bed and cover my head

under the blankets to ward off any evil that might still be lurking there.

Which leads me to think that

perhaps Antigonish wasn’t meant at all to be a nursery rhyme. Maybe it

was simply a compelling and disturbing description of the poet’s own nocturnal delusions,

or of the irrational fear that he shared with children, of “things that go bump

in the night.”

2 comments:

Daniel - Me thinks you think too much and you're too damn smart for your britches!! :)

I guess I didn't sign my name, did I? This is Shelly Bishop

Post a Comment