There’s an

exercise tool called “a prompt” used in a lot of creative writing courses.

Personally, I’ve always thought real writers formulated their own prompts,

which guys like me call “memories” or “topics”, but which trade fiction writers

will usually just call “ideas”. Some will come from the odd offbeat item in a

newspaper or magazine that sets a creative mind thinking. Others will form

around some event or personality in history. Still others might grow around a

psychological term—I just finished reading a book that was about a woman with

“dissociative fugue”, for example. That’s a psychiatric term I had no idea

existed before reading the novel. Nor did the author, apparently, since, in an

interview, she talked about having read the term in a news article and having

become so enthralled that she decided to write a story about a victim of it. In

case you’re intrigued, the book is Love

Water Memory, by my Facebook friend and fellow-writer, Jennie Shortridge.

But, back to

prompts. Although all of the writing I do either springs directly from my mind

or from my constant research, I’ve always liked a challenge. That’s why,

whenever I have a few minutes I can spare, I’m always curious about online

quizzes. Not all online quizzes, but

at least the ones that test areas of knowledge the answers to which any

international journalist worth his salt should know: history, current events,

geography, prominent personalities, etc. They’re a readily available way to

exercise memory, which gets more and more important with age. I usually score

high on them—many are too easy to waste any time on and I’m not kidding myself

that any of them are anything more than click bait—and that makes me feel good,

as Jack Nicholson says in As Good As It

Gets, about me.

I mention this

because something similar happens when I see grammar challenges or writing

tools. And one of my favorite classes when I was studying public translation at

the Argentine business university UADE in Buenos Aires was based on a book

called For and Against in which

students were given pictorial prompts that they were asked to write about. That’s

why I can hardly pass up the opportunity to read a set of prompts.

I have to admit,

however, that they are usually disappointing, and highly unlikely, when not

utterly outlandish. But just for fun, indulge me while I tackle a few.

Name

the most terrifying moment of your life so far.

I could probably

say, quite credibly, that this was when I had a life-threatening accident and

was bleeding out internally and, in the ambulance I heard the assistant tell

the driver he couldn’t find a pulse any more. Oddly enough, however, I didn’t

find that moment terrifying at all. On the contrary, right at that instant, in

a physical state of suspension in which I felt no pain or urgency, when it was

sort of like I no longer had a body to worry about, I felt incredibly calm. All

I wanted to do was sleep, and I heard a voice in my head that said, “This is a

lot easier than I thought it would be. You just close your eyes and let go.”

Fortunately, my

life depended not on my own volition but on the stubborn persistence of

emergency and hospital personnel. Which is why I’m still here writing this

today.

I’ve had a few experiences

in my work as a journalist that should have been terrifying, perhaps, but

journalism’s a lot like the work of firefighters or law enforcement in that.

When everybody else is running away from a dangerous event, you need to be

running toward it. In those moments, you’re the job, so you aren’t usually

concentrating on how scared you are.

Maybe the most

terrified I’ve ever been, however, was during my first couple of days in the

Army. Mostly because it was like being snatched out of everything I’d ever

known and the soft existence of small-town life, only to be dropped into the

midst of what seemed like a nightmare. A place stripped of comfort, where

everything was very hostile, and where the job of the DI’s was to scare the

bejesus out of the recruits, to take everything away from you and give you back

only what they wanted you to have and be.I’m sure for

guys with tough upbringings in hostile environments it was a lot easier,

because they had the tools to deal with it. But for guys like me, and for guys

who were even more naïve and

protected than I was, the first couple of weeks were a living hell, which was

about how long it took to realize that your old life no longer existed and that

you were a soldier now.

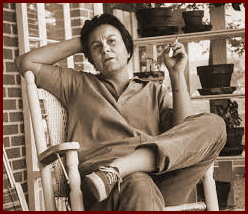

What

famous person do other people tell you that you most resemble?

|

| Papa... |

This is an easy

one. Hemingway. For those of you who say, “Yeah, but you don’t look anything like Hemingway,” all I can say is that I

agree with you completely. But there you have it. People see a paunchy

heavyweight with a white beard and steel-rimmed glasses, and the image is

immediate: Hemingway.

As I writer, I

only wish I could have that kind of recognizability

and writerly fame. Alas…

I always spend

some time in Miami when I’m back in the States and I never make a trip there

that somebody doesn’t say, “Did anyone ever tell you that you look just like

Papa Hemingway?” And every time, I say, “Personally, I don’t see it, but

thanks.” And I mean it, because if I actually did look like Hemingway, well, there are a lot worse people to look

like. I mean, imagine if they told you that you looked like Charles Laughton,

or Peter Lorre. I mean what do you say? “Um, thanks?”

|

| ...and Dan...Who''s who? |

Last guy who

said it was a bartender last May in Downtown Miami. I sat down at the bar,

ordered a beer, and the guy says, “Hey, did you ever compete in the Hemingway

Look-Alike Contest down at Sloppy Joe’s.”

“Nope,” I said.

“You should,

man. You’d win.”

“Only problem

is,” I told him, “by the time Papa was my

age, he’d been dead eleven years.”

Took him a

minute to figure that one out. He went over and served a few drinks elsewhere

then came back. “So how old are you?”

“Seventy-two.”

“Damn, you sure

don’t look that old.”

“How about

another beer?” I said. “And one for you on me.”

What

is the strangest thing you’ve ever eaten?

People who

aren’t from Argentina or Uruguay would think a lot of the things included in

the typical asado criollo were quite

strange. Everything from sweetbreads, to kidneys, to blood sausage, to chinchulines (crisp-barbecued beef or

sheep small intestines) besides abundant beef cuts. But I was always partial to

asado and there was never anything in

it that I didn’t thoroughly enjoy—with the exception of only very occasionally

included udder, which I always found rubbery and tasteless.

He pushed the

plate a few inches away and said, “That’s called intestine and I ain’t eatin’

it!” He was right, but he had no idea what a tasty delicacy he was missing out

on.

The strangest

thing I ever ate, however, according to my taste at least, was when a fellow

correspondent and his wife invited my wife and me to dinner one night in Buenos

Aires. She had previously been married to a Japanese national and had lived a

number of years in Tokyo. So she was the one who called the restaurant,

inviting us to go to the city’s only authentic Japanese eatery.

I’d been saving

up appetite for supper and, typically, we’d had a load of cocktails at their

place downtown before going to the restaurant, so I was starving. I said that

since she knew the place and the cuisine, perhaps she should order for all of

us.

Now, I’ve always

been good about trying new things, but when the dishes started arriving, I was

appalled. It was the first (and, I might add, last) time I’d ever seen sushi

and I wasn’t even sure how to approach it. I was kind of waiting for a little

charcoal stove to arrive at the table because this looked like something that

might involve do-it-yourself cooking. But no, Emily, the hostess said cheerily,

“Well, dig in!” and started transferring strands of seaweed and hunks of bait

to her plate.

Virginia, my

wife, who was at least as hungry as I was, looked like she was about to stab

somebody with her fork and glanced at me like, “Are you kidding me?” But I

didn’t want to offend our hosts so, little by little started working my way

through some of the little seaweed and raw fish bonbons on the serving plates.

I had thought it might end up being a nice surprise and that I’d find I loved

it. It wasn’t and I didn’t and I swore this was the last time I’d be dining on

baitfish chum and marine algae. I found it utterly revolting, and couldn’t help

thinking I might end up with a tapeworm long enough to tie up the kitchen staff

before I set the place on fire.

To make matters

worse, the whole time I was nibbling on raw everything, I was catching

wonderful whiffs of the most delightful barbecued beef smells, which, on our

arrival, I could have sworn were wafting from the kitchen. When Emily said,

“Now we should try some so-and-so,” I said, “Not for me, thanks. I’m stuffed.”

And rose to go find the restroom.

A waiter pointed

me in the direction of the men’s room, back by the kitchen. Along the way, I

had to pass by a little private alcove where the presumed owner and his family

were dining. To my chagrin, and feeling I’d just been had, I saw that they were

contentedly chowing down, not on sushi, but on the most delectable Argentine

beef you could ever want, and washing it down with a good Mendoza cabernet.

Do

you believe honesty is the best policy?

This should have

a yes-or-no answer, I suppose, but it doesn’t. Not for me at least. If the

honesty we’re talking about has to do with our everyday dealings and

transactions with other people, then yes, I do. It may sound old fashioned, but

I think a person is only as good as his or her word and that there’s only one

chance to prove it. Cheat me once, shame on you. Cheat me twice, shame on me.

Once a person lies, cheats, or reneges on a deal or a promise, there’s no going

back. Their word is no longer their bond and there can be no believing them in

the future.

Another such job

is being a spokesperson for a multinational, a billionaire magnate, or a

politician. Those are jobs that intrinsically involve lying or altering facts

to fit a narrative. Journalism is not supposed to be like that and in the best

publications, it isn’t. Stories and facts are meticulously checked and

rechecked and updated as new data becomes available in order to make every

attempt to write the truest version possible of any given story. And reporters

who don’t adhere to those rules end up getting caught out and fired, and will

have a hard time finding a job in any serious medium after that.

But ever since

the advent of “infotainment” (the combination of information and entertainment

that has become a popular branding device in certain cable “news” operations

geared to “spinning” the news rather than reporting it), what sometimes passes for journalism isn’t. And

consumers get confused, because, unfortunately, there are apparently no laws

that require infotainment to be identified as such.

In my own case,

I never worked for a publication that spun the news, nor would I have. In fact,

I was once offered a free-lance opportunity to work for the infamous National Enquirer as one of their

correspondents in South America and turned it down flat, even though their pay

rates were two to five times higher than those of any of the other publications

I was working for. When the editor who contacted me asked why I wouldn’t take

the job, I told him thanks a lot for the offer but if I ever decided to write

fantasy, I’d become a sci-fi novelist.

Speaking of

which, the term fiction is generally a misnomer. I remember bumping into an old

newspaper colleague once who had recently decided to take a year or so off and

write a novel. I asked him how it was going and he said, “It’s hard. After so

many years of being a newsman and having to write the truth, it’s hard to write

fiction and lie.”

I think my jaw literally

must have dropped, because he looked at me for a second and then said, “What?”

“Well,” I said, “we

may have a different idea of what we refer to as fiction, but to my mind,

fiction should be the truest thing you’ll ever write. And what it certainly

isn’t is lying.”

All of this

aside, however, honesty is not always the best policy, at least to my mind. We

all lie in one way or another. Even those who say they never do—that’s a lie

right there, it almost can’t help but be.

I’ve frequently

found that the people who pride themselves on “always telling the truth” either

have a very subjective idea of what the truth is, or they fancy that what they

“believe” and what they “think” is the truth and that everyone else is living

in Fantasy Land. In other words, they’ve declared themselves Owner Of The

Truth. That seems to go with an obsessively blunt personality. That is, they

think that they are obliged to “tell

the truth” whether anyone else wants to hear it or not. So if you ask them

questions like, “Does this outfit make me look fat, or does this haircut make

me look old?” they will answer “honestly” that, “Yes, you look fat as a pig and

it’s not just the clothes!” or “Yes, you look older with that haircut; in fact,

you look ancient!” You would have to be a masochist to be grateful to them for

their response.

Furthermore,

what does anyone gain by that sort of “honesty”? I suppose a coldly objective

person might be able to see an upside, even if it escapes my comprehension. I

mean, I recall a girl in high school who was a couple of years older than I was

and about whom my sister told me a story that, at the time, made my blood boil.

The girl in question (Sue, we’ll call her) had a shy, sweet personality and a

kind, pretty face. She was what I might have referred to as “pleasingly plump”,

but the fact that she didn’t fit the accepted standard of what the “cool girls”

in school looked like, meant she wasn’t all that popular.

It seems she

once confided to a friend that there was a boy on the football team whom she

had loved from afar since grade school. Back then, before puberty and incipient

sex started getting in the way, they had been friends and playmates, but since

junior high, he hadn’t given her the time of day. The friend whom she’d

confided all this to was indeed one of the popular girls, and knew the guy in

question. So she decided to help her shy friend out and told the guy that Sue

was crazy about him and asked why he didn’t ask her out.

The guy laughed

derisively and said, “Well, if I could fit her through my car door, I might!”

Now this would

have been no big deal if Sue were none the wiser. Her friend could have written

the guy off as a jerk and never said anything to Sue about it. But this friend

of Sue’s was one of those “honesty’s the best policy” people who felt obliged to tell her friend what a cretin

the guy was to keep her from pining after him anymore. So she could think of

nothing better to do than to tell Sue

what the guy had said. Honesty, clearly, but, the best policy? To my mind, it

was just unnecessarily cruel and subjective, and who’d asked her, anyway?

Some would say

the story had a “happy ending”, since, because of that incident, Sue went on a

diet, started working out, learned all about how to use make-up and clothes and,

before graduation, had become one of the most popular girls in school, a girl

who could pick and choose whom she wanted to go out with.

But my question always

was, how much did she have to suffer to make those changes, and at what cost to

her personality, happiness and self-esteem? More importantly, what does it say

that the reason she made all those self-improvements didn’t spring from her

desire to mold her own destiny, but from attempting to make somebody else eat

his words and see what he was missing? Seems to me the football jerk was being

given way too much importance, but I guess only Sue would be able to say

whether she was grateful for her friend’s “honesty” or not.

And finally…

If

you joined the circus, what act would you most want to perform?

Saved this one

for last because it’s the most typical of the typically outrageous things these

self-help writing courses include. But never mind, I actually have an answer on

the tip of my tongue.

When I was

sixteen, I started working for the then-biggest music store in Lima, Ohio. I

sold musical instruments, took inventory and did just about anything else

around the store that my boss, Bruce Sims, asked me to do. But I also gave

rudimental drumming lessons—meaning, beginning, intermediate and advanced snare

drum lessons based on the twenty-six rudiments that every percussionist needs

to know.

Now the store

was near the main square in downtown Lima and was a veritable hub for musicians

from all over the area, that covered at least three West-Central Ohio counties.

So, working there, you were bound to meet every major musician, band and

orchestra director, and private music teacher in the region. And you also made

contact with a lot of people associated with music, entertainment and musical

instrument manufacturing. For an ambitious teen musician, it was an exciting

place to work, a place where you could feel at home.

But—as usual—I digress.

Manager Bruce Sims knew just about everybody there was to know in the business

in Ohio and elsewhere, and some of the most unlikely people you can imagine

would drop by to say hello to him whenever they were in town. One early summer

day, half a year before I would turn eighteen, I was standing behind the

counter and Bruce was at his desk on the sales floor when this big guy walks in

the front door and Bruce says, loud enough for him to hear, “Oh-oh, here comes trouble.” Then they both

laughed, exchanged hearty handshakes, and sat down at Bruce’s desk to talk.

|

| Dan - Drummer |

I went about my

business while they chatted, sold a girl some reeds for her clarinet and a guy

a pair of drumsticks. But just then I overheard Bruce say, “Yeah, I’ve got one

standing at the counter over there.” When I looked up from whatever it was I

was doing, I see both Bruce and the guy looking my way, Bruce with his usual

wry grin.

“One what?” I

said. And Bruce, turning to the guy, said, “Best rudimental drummer money can

buy.”

“Okay if I

borrow him for a minute?” the guy says, and Bruce nods and says, “Sure.”

So the guy comes

over to where I’m standing, introduces himself, shakes hands with me and says, “I

used to be a musician here in Lima. That’s how I know Bruce.”

“Used to be?”

“Yeah, played a

little trumpet,” he says. “Never much good, strictly a hack. But I like to stay

close to it.”

“What can I do

for you?” I ask.

“Well, for a

number of years now, I’ve been a talent agent for a traveling circus.”

“Really?

Interesting job. Never met anybody from the circus before.”

The guy smiled

and nodded. Then he said, “Anyway, we’ve got a little brass band that travels

with us and our snare drummer’s retiring.”

That was back

before the Cirque du Soleil with its distinctive avant garde music. Back then, circus was all about Sousa marches

and can-can burlesque. So rudimental drummers, parade drummers, were what a

circus band would be looking for.

“They asked if I

knew anybody,” the guy went on. “I said I did and dropped by to see Bruce. I

know if Bruce says you’re the guy, his word’s good as gold. Interested?”

“Interested in

what?”

“In playing with

the circus.”

“Wow,” I said,

stupidly, “Uh, well…”

“Pays ninety-five

bucks clear a week and the circus pays all room, board and travel while you’re

on the road.” Back in those days, the mid-sixties, that sounded like good money,

considering that it was clear and all expenses paid.

I said, “I guess

I should tell you that I’m still in high school.”

“No problem. You

can do the summer tour with us and see if you like it and if we like you. The

rest we can work out later. Get us a letter with your parents’ permission and

we’re cool.”

“Can I think it

over?”

“Sure, but not

indefinitely. I’ll be back this way in a couple of days.”

By the time I

was driving home to nearby Wapakoneta, I was feeling really excited. Playing

with a circus band! You didn’t get an opportunity like that dropped in your lap

every day.

Reba Mae had

other ideas though. What about college, my mother wanted to know? And the circus! Did I have any idea the

class of people that were in the circus? And what about the draft? It was the

height of the Vietnam War, and if you weren’t in school after graduation, Uncle

Sam would make sure you were in the Army. Did I think the Army would let me

just keep traveling around with the circus after high school?

Whitie, for his

part, heard me say I might join the circus and said, laconically, “Do whatever

the hell you want, Dan. You always do anyway.”

But Reba Mae

eventually wore me down and the circus became a could-have-been fantasy.

Years later,

working in a newspaper in Buenos Aires, I had a colleague who, when things got

chaotic, would always say, “I shoulda taken that job in the bank.”

And I’d respond,

“I shoulda been a drummer in the circus.”

Prompts. Toss a

writer a few and, no matter how unlikely they are, he’ll tell you stories all

day.