Continued

from Part Two

https://southernyankeewriter.blogspot.com/2022/01/maybe-thomas-wolfe-was-rightmaybe-you.html

“This is a man, who, if he can remember

ten golden moments of joy and happiness out of all his years, ten moments

unmarked by care, unseamed by aches or itches, has power to lift himself with

his expiring breath and say: "I have lived upon this earth and known

glory!”

―Thomas

Wolfe—

You

Can’t Go Home Again

The somewhat reluctant helping hand I got from my parents—reluctant on my father’s part, anyway—seemed to change my luck. A friend who was the CEO/publisher of an up-and-coming business magazine in Buenos Aires offered me a job reporting and translating for his organization. I had known this guy, Gabriel Griffa and his partner, Marcelo Longobardi—who was now on the verge of becoming a very well-known radio and television personality—since they had founded Apertura, their magazine, a decade earlier. Back then, they had both been college students, barely out of their teens, and had put their first few issues together on a table in a bar because they still didn’t have an office.

The result was lively, chock-full of

interesting stories and excellent writing, and it was a publication that sought

to take the best in avant garde style from premier US magazines like Rolling

Stone, Esquire, The Atlantic, Forbes and Fortune, but in Spanish. I was twelve years older than they were with

nearly a decade of experience under my belt and had helped them with contacts

and publishing tips when they were first starting out, as well as treating them

to lunch whenever I could at a couple of good restaurants where I had credit

from advertising swap-outs at the newspaper.

They hadn’t forgotten me now that they

were becoming two successful young entrepreneurs. I should have jumped at the

chance without hesitation, but, as I said earlier, I had just been gravely ill

and was still recovering. Since every place I’d worked in the media, I had

ended up in positions of responsibility and authority, I wanted to ensure for

the moment that this job wouldn’t be putting that kind of pressure on me.

At first, I accepted a lower-level

monthly salary simply to be the house translator. The magazine made use of a

lot of licensed articles from major international magazines. My job was to

translate these pieces from English to Spanish. I always dealt with

correspondence between Apertura and the English-language publications

they sought rights from. I worked closely with the general news editor and

liked that. Alicia Cerri and I had known each other for some time. She was,

like me, a veteran journalist with an old-school approach to the news. She

understood what had just happened to me, even though I didn’t discuss it openly

with her. She’d clearly been-there-done-that too, I figured, before she’d come

to Apertura.

|

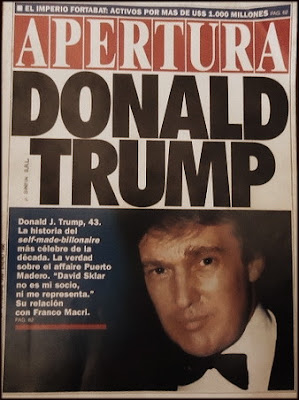

| We were already doing in-depth research on Trump back then at Apertura. |

I liked the job. I was in the editorial

department again, I was an older, respected newsman whose reputation most of

the staff knew, and I got to talk daily with journalists as their colleague

rather than as their boss. But in terms of what I did, it wasn’t any more

stressful than a nine to five office job.

As she saw me getting stronger and showing

more and more interest in the day-to-day of the magazine, Alicia started pitching

stories to the publishers that she thought were right up my alley as an

investigative reporter and commentator. I started with one that was sort of “science-fiction”,

for an entire issue that the magazine was doing on The Future.

They asked me to write on the future of

media. This was the latter part of the eighties. Internet Services Providers

wouldn’t even emerge in the US until 1989. But as I say, Apertura was an

avant garde magazine, so we were already doing a great deal of research

on the incredible advancements in resource and information-sharing. After many

hours of research, I came up with a sort of “artist’s conception” of what I

figured the future media would look like. I accurately foresaw the future

struggle to be faced by print media and the advent of worldwide electronic

communications.

It was hilarious because I was a

tech-dinosaur, a literary Neanderthal who was writing this piece on an old manual

Olympia typewriter. But at one point, it was like a revelation, a prescient

moment in which I wrote that, someday, not too far distant in the future, guys

like me, who made their living doing research, commentary and translating,

would be able to do it all online, with access to more and better information

than they could ever possibly use. They would, I said, be able to work from

anywhere, as long as they had a satellite signal. Even, I suggested, from a

cabin in the mountains in the middle of basically nowhere.

|

| In my home studio in the post-Herald days. |

As I wrote it, I was just letting my

mind and imagination fly. I figured this would all happen when I was long dead

or too old to care. Nobody could have told me then that, half a decade later, in

1994, I would be doing just that from my mountain home in Patagonia.

Anyway, the publishers loved the story and

started asking me to do more stuff. I said, look, it was one thing to write a

lyrical essay like this one, but I was an English-language writer.

Spanish-language journalism was a whole other ball of wax. I didn’t have the

tools, the style, or the jargon for it. “Anything

I write,” I said, “is going to sound like an American magazine article in

Spanish, not like an original Spanish-language piece written by an experienced

Argentine writer.”

That, they said, was exactly what they

wanted—an article in eloquent Spanish that sounds like a Yankee magazine. “And

your writing in Spanish is better than that of half the local people we’ve got

writing for us.”

Suddenly, I was feeling good about

myself again. I wasn’t sure what had happened to me, how I’d fallen so low, but

I was back! And I was being recognized for the professional that I had become. By

a few months later, I had gone from being assigned brief single-source pieces

with minimal reporting to doing secondary research articles with considerable “leg-work”

and a number of interviews, and, finally, to being asked to do two major cover

stories.

But as I got deeper and deeper into the

profession again, I couldn’t help remembering how I’d gotten here. And after

the crisis I’d just been through, it was no longer just about “having a job.” I

was, at heart, an American writer. My language was English, no matter how

fluent I might be in Spanish. And I blamed the fact that I’d lived nearly

twenty years on a market where what I wrote in was a second language for my

lack of opportunities to reach success in my culture of origin. It might work

okay for journalism because here, I, like other foreign correspondents, was a

novelty. An English-speaker who was an expert on a Spanish-speaking region of

the world. That meant that what I brought to the table wasn’t just my craft as

a reporter and writer, but also a deep understanding of an entirely different

culture and of how it operated within the context of the world order.

I tended to forget this last all-important

aspect of my craft when I fixated on “going back home”. My idea was that,

surely, one or the other of the publications I had worked for abroad would be

interested in hiring me as a reporter when I returned to the States. Once I

landed a steady job in a major city, I figured, I would continue developing my

creative writing in my spare time and would finally be on a market where I

could pitch my creative fiction and non-fiction to US agents and publishers.

I had it all figured out.

My confidence improved and my health

restored, after about a year of working and saving, I decided that it was now

or never, if I was ever going to “go home again”. A major stumbling block was

the fact that, for Virginia, going to the US to live wasn’t a matter of “going

home”. It was all about leaving home. Leaving behind her country, her

city, her family, her life. Although she had enjoyed the fun of being an

exchange student in high school and college, she had quickly learned, when I’d

first been discharged from the Army and we returned to Ohio, that it was one

thing to be a cultural exchange guest in that society, and quite another to be

“just some foreigner” in a place, like many in America, that was not

particularly friendly toward “aliens”.

|

| Virginia was already home. Why would she ever want to leave? |

During the first six months that we

struggled to make a living after I was discharged from the Army back in 1973,

she had suffered on-the-job isolation, discrimination and racism. It was her

first-ever experience with any of these things, and it broke her. She became

clinically depressed and eventually became nauseous and dizzy every time she

had to leave our rented apartment in Lima, where she also felt looked down on.

She had loved living in Europe, during my final posting in the Army, but now, in

the rural and industrial Midwest, she was impossibly homesick and inconsolably

sad. Never had the word “alien” been more fitting. She may as well have been a

Martian as an Argentine.

That was why I had originally made a

decision to go live in her country “for a year” and ended up staying for nearly

twenty. But now, I was passing her the bill for that. I was basically saying

that if I had forged a life as an expatriate in her country for all those years,

perhaps it was time she should try living in mine for a while.

It wasn’t the same. Not at all. Even back

then, in the nineties, the US had become a country that had forgotten that the

vast majority of its citizens descended—as Jorge Luis Borges once quipped—“from

boats” rather than from any native culture. And now the sons and daughters and

grandchildren of the immigrants who had populated the United States shunned as “aliens”

the new immigrants in their midst.

In Argentina, on the other hand, I had

seldom been treated with hostility for being American, except by people on the

extreme political fringes. On the contrary, being an American had, ninety

percent of the time, played in my distinct favor. Given how the US had always treated

Latin American citizens from the Mexican border to sub-Antarctic Ushuaia, I

might well have expected, as a Yankee, to be drawn and quartered and fed to the

rats as soon as I arrived. But I had nearly always been treated with friendly

respect by the vast majority of people.

Still, that was my line of reasoning,

and I was sticking to it. I came to your country with you, now you go to mine

with me. But if it came down to that, I couldn’t be at all sure how she would

react. Realistically, however, I figured the most likely scenario was her saying

that she was where she wanted to be. She was home. That I’d had plenty of time

to make it my home too. But if I wanted to be somewhere else, it was my

decision. I should go if I must. But I would have to go alone.

I was no good at discussing such

emotional issues. I did my best thinking on paper. If I had to debate a

difficult case like this aloud, the flood of emotions it was sure to bring up

would surely stand in the way of saying what I wanted to say and how I wanted

to say it.

So I wrote Virginia a letter. I tried my

best for it to be dispassionate, logical, clear-cut. The last thing I wanted it

to sound like was an ultimatum. But no matter how I sought to cut it, an ultimatum

was precisely what it sounded like. Like “either/or”—like “either-or else”.

No matter how eloquently, no matter how lovingly I tried to put it, the ultimate

message was the same: “I’ve come to a decision: I’m leaving. Come with me if

you want to or stay here if you don’t, but I need this to survive.”

Reluctantly, she acquiesced.

We arrived in Miami in mid-January of

1991. My father and mother were wintering at their condo in Ocala. Whitie had

made it clear that he wasn’t about to “try and drive in goddamn Miami,” so we

rented a car to make the five-hour trip from Miami International to Ocala.

We parked in a guest space in front of

their place in the condo complex. If was the first time we’d been there. Reba

Mae was evidently watching from the window because as soon as we got out of the

car and started getting our luggage out of the trunk, she appeared at the top

of the steps to their second-floor apartment.

“Did you have any trouble finding us?

Oh, it’s so great to see you both. Come in! Come in!”

When we got inside, Whitie was waiting

in the entryway. Virginia gave him a hug and then she and my mother went off

for a tour of the condo. I was still standing there with a suitcase on either

side of me saying hello to Whitie. We shook hands, gave each other a stiff,

perfunctory hug and then he laid his right hand on my left shoulder and looked

as though he were about to say something important to me. Perhaps that he was

glad to see me, that he’d missed me all those years, that he was happy I’d

finally decided to move “back home”.

Instead, he leaned in close and lowered

his voice so my mother and Virginia wouldn’t hear, and said, “Hey Dan, have you

got that five grand I loaned you, because I need it.” Right there in the

entryway, I dug out one of the envelopes of cash that I had distributed between

Virginia and me and which represented the scant capital that we had been able

to put together for a fresh start in the US by closing out our bank account and

selling whatever we could before leaving Argentina. I removed its contents and

counted out fifty crisp new hundred-dollar bills, placing them in my father’s

outstretched hand.

“Thanks Dan,” Whitie said. And then,

with, what seemed to me, hollow concern in his voice, he said, “You gonna be

okay with what you’ve got left?”

I said, “Guess I’m going to have to be,” and then carried our suitcases away in

search of the spare bedroom.

I had wanted to drop the rental car in

Ocala, but Ocala didn’t have a rental agency branch. The closest one was Daytona

Beach.

We

were all having a cup of coffee that Reba Mae had brewed and were sitting

around talking. I said, “Listen, before we get too settled in, I have to turn

in my car. Think you could drive over with me in your car and bring me back,

Dad?”

“Sure.”

“Good. We better get started. The drop

is in Daytona Beach.”

“Daytona! Geezus, Dan, why so

far? That must be a good hour and a half from here!”

|

| Whitie and me in Ocala |

“Oh come on now, Dan,” Whitie said incredulously,

“You mean to tell me that there’s no place to drop it off here?”

“That’s exactly what I mean to

tell you. You think if there were, I’d want to drive all the way to Daytona

when I just drove five hours up here from Miami?”

“Well, that’s sure a helluva note,”

Whitie complained.

“Well, sorry,” I said, “but I can’t

drive two cars over there, so if you’d like to lend me a hand…” I trailed off.

“Let’s all go!” Reba Mae said

enthusiastically. “It’ll be a fun drive.”

In the first couple of weeks that we

were in Ocala, however, Whitie showed his enthusiasm and caring in other ways.

One of my first tasks was to find us a serviceable vehicle. When I asked Whitie

if I could borrow his car a few hours, he said, “Where ya goin’?”

“To look for a car to buy,” I said.

“Well, pardon me for saying so, Dan, but

you’ve never been much of a horse-trader. How ‘bout if I tag along.”

“Sure,” I said.

I really had no problem with that. My

father knew cars. And he was the kind of negotiator who beat sellers down until

they were practically ready to give the cars away just to be rid of Whitie.

Furthermore, he knew exactly where to go. So we all got into his big Mercury

Grand Marquis and made an outing of it.

We drove straight to an enormous used auto

mart on Southwest 17th Street in Ocala. On the way, Whitie asked me

how much I wanted to spend and what I was looking for. I said I preferred a van

to a sedan, but that I didn’t, obviously, have a lot to spend, so I wanted the

best vehicle I could get for the least amount of money possible.

The salesman’s name was Del Río. He was

a small, nervous man in his thirties. He was a fast talker and wore

sunglasses—even indoors. I said I was looking for a van, but that I wasn’t

going to use it to work, so economy was more important than a huge engine.

“Your best bet, then, is a mini-van,” he

said. “Roomy, comfortable and great mileage. What model are you looking for?”

“Not sure,” I said, “But with the money

I’ve got to spend…”

“We can set you up with financing,” Del

Río said.

“No, cash,” I said shaking my head. “I

figure maybe five or six years old, say.”

“Definitely a mini-van then,” he said.

“How mini’s mini?” I asked, by now more

familiar with European cars than I was with late-model American ones. He

signaled me to follow him. Whitie and I trooped over to have a look-see while

Virginia and my mother waited inside.

We made our way down a long corridor of

cars and trucks parked side by side according to type, make and model. The two

he showed me were across from each other—Chevy on one side, Chrysler on the

other. “This is an eighty-five Chevrolet Astro,” Del Río said, doing a Vanna

White with his left hand toward the Chevy line, and then repeated the gesture

with his right, saying, “And this is an eighty-six Dodge Caravan.”

Whitie and I looked at the interiors of

the two vehicles, walked around them both, checking out the paint and body,

kicking the tires and measuring the depth of their treads with our thumbnails

while Del Río stood by, in desultory fashion, smoking a Marlboro. We opened the

hoods, peered in at the engines and wiring. Whitie stuck a hand in and wiggled

this and that. Then we dropped the hoods and turned to the salesman.

“What are you asking for ‘em?” said

Whitie.

“Fifty-nine hundred for the Chevy and seven-nine

for the Chrysler.”

“Geezus!” Whitie said. “That’s goddamn

highway robbery!”

“Very serviceable vehicles,” Del Río

said. “The former owners are both old customers of ours. These are both

cream-puffs.”

“They better be cream-puffs with hot fudge,

nuts and cherries for those prices,” Whitie said. Then, “So can we take ‘em for

a spin?”

“Sure. Let me just go get the keys.”

When the salesman left, I said, “I

really like that Chrysler. But I can’t afford that kind of money right now.”

“Oh hell, Dan,” Whitie said. “Don’t

worry. You won’t pay anywhere near the asking price for either of them.”

“What makes you think so?”

“Trust me. It’s January! See how many

goddamn cars they’ve got on this lot? They’ve gotta clear out their inventory

before tax time. He’s on a fishing expedition with those prices.”

Del Río came back with the keys.

“We’ll be back shortly,” Whitie said.

“Great, I’ll wait for you inside.”

We took the Chevy out first. Whitie said

it had some road noise up front, which might mean the front end was about shot.

It also felt sort of doggy to drive. No pick-up, like maybe the engine wasn’t

in the greatest of shape. Then we drove the Chrysler, and I fell in love with

it.

“But it’s got a helluva lot of miles on

it,” I said.

“Yeah,” said Whitie, “but did you see

the engine? That’s no Chrysler motor. It’s a Mitsubishi. It’s only got a

hundred thousand on it and those Jap motors’ll do two hundred without ever

having to do any maintenance on ‘em, so I wouldn’t worry much about that if it

runs okay.”

“Runs like a rabbit.”

“There ya go, then.”

“Okay,” Whitie said as I drove up in front of

the show room, “Let me do the talking, okay?”

“Fine with me.”

“Didn’t I tell you that was a great

car?” Del Río beamed as we pulled up and he came out of the building.

I smiled.

Whitie said, “Not for that price, it’s not. That car has some issues. For one thing, geezus, it’s almost been all the way around the damn globe.”

“Oh, don’t worry about that, Mr.

Newland,” Del Río said. It has a Mitsubishi four-cylinder, powerful little

engine that gets good mileage and they’ll literally run forever.”

“Who the hell told you that fairytale?”

Whitie said with a grin. “We fought the Japs during World War Two and now we’re

buying engines from them for American cars? Not sure how I feel about that.”

“Great engines!”

“Yeah, say them.”

“Well,” said Del Río, “let’s go inside

and see if we can’t make a deal.”

Inside, Virginia joined Whitie in the

assault on our salesman. As he was telling us all of the wonderful features of

the vehicle and trying to convince us that we would “never find a more

impeccable previously owned automobile,” Virginia suddenly said, “Excuse me, but would

you mind taking off your dark glasses?”

The guy looked at her like, “Come

again?”

“I’d like to be able to see your eyes

while you’re telling us all this.”

Del Río flushed to the roots of his

short-cropped hair, but removed his glasses, and kept talking. The poor guy had

a cast in one eye that made him look like he was looking at you with one eye,

while mounting a lookout with the other to make sure nobody was sneaking up on

him from the side. Before long, Virginia repented, said, “Sorry, you can put your

glasses back on,” to which he said, “Thanks,” and did so.

“If you want us to buy it,” Whitie said,

“You’re gonna have to come way the hell down on the price.”

|

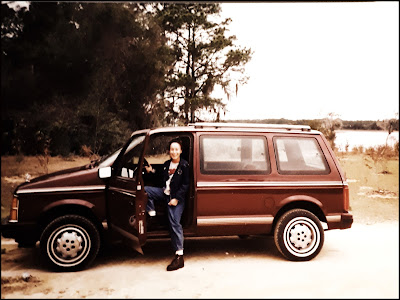

| The Caravan - thanks to Whitie, ours for a song |

“Just a minute,” said the salesman, “let

me go talk to the manager.”

After he’d left, my father said, “Yeah

right. Talk to the manager. He’s gonna go talk to a Marlboro and be right

back.”

About a cigarette’s-worth later, Del Río

was back. “Well, I got you a great discount. We’re knocking off a thousand

bucks. Six-nine instead of seven-nine.”

Whitie looked disgusted and said, “Come

on, Dan. Let’s go down the road.” And we started toward the door.

“Wait, don’t go. We’re negotiating here.

How much would it take for you to drive this car off the lot today?”

“I don’t know,” Whitie said. “Make me a

serious offer and we’ll see.”

“Let me go talk to my manager.”

And on and on this song and dance went

for perhaps an hour until it finally came down to “Name your price.”

In the end, we all shook hands, the

administration made out the paperwork, I shelled out three thousand six hundred

dollars cash, and drove the mini-van off the lot.

As we were getting into our cars, Whitie

come over to me and murmured, “See there, your ol’ man got you most of that five

grand back.”

To

be continued…

3 comments:

Eagerly awaiting Part 4, Dan. I felt like I was in Ocala! I lived in Sarasota for some years and I’ve been up 301, through Ocala, and around, many times. I could see and hear that salesman as well as your dad and you. I love your mother asking the salesman to take his glasses off. Very descriptive and engaging! The pictures are vivid!

Many thanks Wayne! I just stood by and lett the ol' man do the talking, hahaha. It was feisty Virginia, my wife, by the way, who told Del Río to take off his shades. My mother was far too shy and retiring to ever do anything so bold. All the bartering made her really uncomfortable, as always.

Thanks so much Joe! Yeah, I think they broke the mold with Whitie.

Post a Comment