My sister Darla and I have more than occasionally talked about our different academic experiences. It’s a pretty one-sided conversation. She’s the only one with any real academic experience worth talking about. She was an extraordinary scholar all through grammar school and college, while I was...not. She graduated from high school very near the top of her class and maintained a lofty GPA throughout her undergraduate studies at Miami University and her graduate studies at Case Western Reserve in Cleveland.

|

| First grade...sigh |

I followed her through grade school and high school like a

three-year-long, delayed-reaction shadow, and if I’d had a buck for every time

one of her former teachers looked expectantly at me on the first day, only to

repent within a couple of weeks, I could have paid my way through my first of

four years of college. Their lament was always the same: “Oh Dan,” they would

say, shaking their heads sadly, “I wish

you could be a little more like Darla!”

I wanted to say. “So do I!” and would have meant it, but I was afraid

the words would ring hollow. What I couldn’t figure out was how they, as

educators, even thought that was possible. Couldn’t they see that my beautiful

sister was also a genius and that I was a gawky, geeky moron?

It was no-go from the get-go as the first teacher I quickly

disappointed, then irritated, was my first grade teacher Miss L. She was an

irascible, red-faced lady with a quick temper worn thin by way too many generations

of six-year-olds and who had a spare-the-rod-spoil-the-child mentality. Except

that she didn’t have a rod, but a paddle. It was probably confiscated from one

of her charges. One of those rustic toys known as a “paddle-ball” that you

could buy in the dimestore back then and that consisted of a short-handled but

ample paddle with a red rubber ball attached to an elastic band clamped to the center

of it. The objective was to bounce the ball on the paddle as many times as

possible without missing, and the elastic band was to keep the ball from getting

lost. But the band was the first thing to go, and then the ball would end up in

your dog’s jaws, and the paddle would lie around abandoned and useless. One

more thing to clutter up the toy box.

Well, Miss L saw a non-conventional use for it and repurposed the one

she had inherited as her personal “board of education”. It looked to be old and

well-used and surely was teeming with traces of DNA from a countless parade of

first-grader tuchuses. I bore witness

to several pupils receiving the business end of that paddle—or rather,

witnessed the sharp slapping sound of the paddle whacks and heard the kids’

cries, because she always took her victims to what was rather grandly known as

the “cloak room” (a little divider at the back of the classroom behind which we

hung our wraps in winter) and God help you if she caught you looking any way

but at the blackboard when she returned.

Suffice it to say that I was terrified of being on the receiving end of

her wrath. If because of having known Darla first her expectancy regarding me

was dashed from the first week of first grade, mine regarding her fell just as

short. Since Darla was one of her star pupils and a particular pet of hers, my

sister’s perception of Miss L was quite different from my own. Darla always

elicited the teacher’s smiles and kind words, so for her, Miss L was the best

teacher ever. The face I saw was quite often full of irritation and disgust. To

begin with, I was left-handed. For

teachers of Miss L’s generation, that was two strikes against you right there. Our

school system, by then, no longer allowed the old-timers to “change” southpaws,

but I’m quite certain that if she’d had her way, she would have whacked me

across the back of the left hand with a ruler every time she saw me pick up one

of the giant black pencils they issued us, until I learned to print “normally”.

It took me a while to figure out how lefties write—hand turned around

upside down, making the letters from the top instead of the bottom—in a

right-handed language in which pencils and pens are made to be pulled across

the page from the right rather than pushed across from the left. My contortions

to try and not drag the heel of my left hand through my work, smudging the

entire page with graphite grey made it difficult to form the letters Miss L

drew on the board with anything like finesse, and the tortuous results were

obvious in my disastrous attempts at handwriting, made worse by my erase-and-reset

technique that eventually ripped smudge-framed holes in the page. Hardly an

assignment that I turned in came back without the words Messy work! written in bright red letters,

in Miss L’s neat cursive hand.

But there were other problems. I found myself distracted and listless when it came to reading the blackboard. Whenever I had to do it, I seemed to glaze over. And this was a problem that would only worsen over the next five years until I got granulated eyelids from too much strained reading the summer before sixth grade. When my mother, Reba Mae, took me to the optometrist he gave me a thorough eye exam and concluded, though in more scientific terms, that I couldn’t see for crap. So I finally got corrective lenses for far-sightedness and acute astigmatism. It opened up a whole new world.

My difficulty seeing the board was made worse by Miss L’s declaring me

“much too talky” and banishing me to the back row. I knew you could get paddled

for just about anything. The year before, Miss L had paddled a cousin of mine

for the crime of “refusing to clean up his plate” at lunch, then, when, with

her standing over him, he managed to swallow the creamed peas he had tried to

avoid, only to start gagging and heaving them up on the cafeteria floor, he got

paddled again. Being so obviously the target of her displeasure, I was scare

stiff that I’d be visiting the cloak room with her before the year was out. To

a six-year-old, it seemed like an awful lot of mindless animosity.

But, miraculously, I managed to get through the first grade unscathed. I avoided the paddle because, I can only imagine, I was Darla’s brother and my mother worked in the school cafeteria. But also, perhaps, because if first grade taught me anything, it was how to sweet-talk my way out of punishment. And then too because, despite my poor eyesight, I was a prolific reader from the outset and had already been taught to read a little by my sister before I ever reached first grade.

My first year could have been worse, I guess, but was still traumatic

enough to sour me on school from the very beginning. Luckily, my second and

third years were spent with a couple of the kindest and most understanding

teachers in the system, who patiently helped me bolster my net-deficit

self-confidence somewhat and to relax a little and enjoy the learning process.

They taught me cursive writing and helped me cope with my

left-handedness to the point that I began to love sitting down with a Golden

Rod yellow pad and ballpoint pen and writing stories in my spare time, at first

mostly just imitating (nay, plagiarizing) the writers who most struck my fancy

as my sister introduced me to the children’s section of the local public

library. Darla was a prodigious reader and I wanted to be too. What I quickly

found out, however, was that I was a much slower reader, if with excellent

retention and reading comprehension. But there was something mildly dyslexic

about my reading skills that sent me back several times over each sentence when

reading silently and which made reading aloud an almost painful process that I

tried to avoid at all costs.

Later in school when there were exams with time limits, I quite often wouldn’t make it to the end before the teacher said, “Pencils down!” So for a long time, I struggled to maintain a C-average, especially since I couldn’t pull up my grades with math because there was also a hint of dyscalculia in my math skills that manifested itself as a kind of exhaustion that gripped me when confronted with mathematical problems. I had no major difficulties with it until later, when more complicated math skills were required, but even then, in the lower grades, I often needed help from my mother to make sense of more than plain addition and subtraction, and when it came time to learn multiplication tables, I had no choice but to learn them by rote through endless repetition, because I couldn’t seem to establish any sort of logical relationship between one number and another in the multiplication formulas. And in writing numbers, even copying them from the board, I had to be really mindful of what I was doing or I would turn them inside-out. For instance, reading 5-2-5 and copying 2-5-2. Clearly, one mistake like that in a column of numbers and I wasn’t going to get the same result as the other kids.

That said, however, my second and third grade teachers instilled in me the

idea that there was nothing wrong with my mind, that I just had a different way

of seeing things and all I really needed was to be more careful and to build more

confidence in myself. And they told my parents so as well.

Indeed, I was struggling with self-confidence. My confidence in anything

and everything was shattered after my dad, Whitie, had his first major nervous

breakdown, when I was five years old. I thought my father was the strongest,

bravest guy in the world. Our family protector and provider. And seeing him

reduced to a shattered, whimpering mess—only to follow up with lightning rages

or euphoric abandon—brought the structure of my world crashing down. It was

like you weren’t always sure who would be sitting across the dinner-table from

you, even if they all looked like Whitie.

Nor were my father and I anything alike. He had been a typical boy-boy

with a penchant for fist-fighting and team sports, and I was happiest when my

nose was in a book, when I was sketching or when I was writing a story. I

loathed organized sports—organized anything, actually. And I was a natural born

pacifist—something my father quickly broke me of by vowing that if he ever

again heard of me being hit by another kid and not immediately beating the snot

out of him, he, Whitie, would whip me himself. Anyway, with such existential

threats to the stability of my home, I, who was, perhaps, more sensitive than

the average boy and certainly more of a natural born worrier that the majority,

found it hard to concentrate on anything else.

Then came fourth grade and Mrs. G. And the lift given to me by the

previous two teachers was suddenly knocked out from under me. She decided from

the outset that I was lazy. She seemed to see a spark of intelligence in me and

figured if my academic performance was less than stellar, it was probably

because I was a gold-bricker. Although she did admit that part of it might just

be that I wasn’t the keenest knife in the drawer. To her credit, I set out to prove

her wrong about this last because I wasn’t about to be pigeon-holed as an “also

ran”, or worse, an idiot. So I strove harder than ever before to overcome poor

sight and learning problems and to pull up my grades instead of accepting

Whitie’s dictum that I was “just like him, average, and there’s nothing wrong

with being average, Dan.” Between the occasional A’s, not infrequent B’s, still

frequent C’s and occasional D’s that I got that year, I managed a B-minus

average. Mrs. G had some rather backhanded praise. She had noted my effort. I

was to keep up the good work, but not be too hard on myself, because

left-handed people were handicapped from the outset, and while I would never be

a brilliant student like her own son, she said, I was still doing fairly

well...considering.

She mentioned her son, who was a year ahead of me, a great deal in class

and, for a while, I grew to instinctively hate him. I don’t think I was the

only one to get sick of the references because once when she was teaching us

how to write a recipe, she dictated, “One full cup of chopped nuts,” to which,

behind me, I heard my cousin Greg quip, “Aw shit, her poor son!” I burst into

raucous laughter along with several other kids who’d heard the barb, but Mrs. G

was not amused.

Oddly enough, her son and I became good friends in high school and even

played in an amateur rock band together...besides pulling some vandalistic

pranks in each other’s company that should have gotten us both thrown in jail. Nobody

would have suspected either of us. One of our other cronies was also a

veritable choir boy, and above reproach. The fourth...not so much. But, man! Was he creative! A logistician by nature, thanks to some of the stunts he

helped us plan, more than once our handiwork ended up in the local newspaper.

The three meeker of the crew, retiring bookworms all, well, we were as elated

as Billy the Kid with the anonymous rep we were garnering. Especially in

possession of the sure and stated knowledge that local law enforcement was on

the lookout for us.

So then, fifth grade with everyone’s favorite teacher, Miss C, who had

also been my mother’s teacher back when she had just gotten her teaching

certificate from Normal School in the 1920s. I felt relaxed and at home. That

year, however, I fell sick with hepatitis. I’ll never forget. My brilliant

friend Tom was attempting to teach me to play chess during lunch hour and I was,

to my utter surprise, actually making headway. Then suddenly, I became acutely,

horribly ill and my mother had to come pick me up and take me home. I was out

of school for over a month—and not myself for close to a year. But when I went

back to class, with Miss C’s kind understanding and tutoring help, I quickly

caught up. I was really proud of this achievement and felt I had grown a lot

during my illness by reading “big boy” books that my mother brought me every

few days from the library on her way home from work. I had hours on end to read

them, confined as I was to my bed, so despite reading slowly, I went through a

real stack of them. Stevenson, Dumas, Twain, Dickens, Hemingway’s Nick Adams

series...I ate them up.

But I never played chess again.

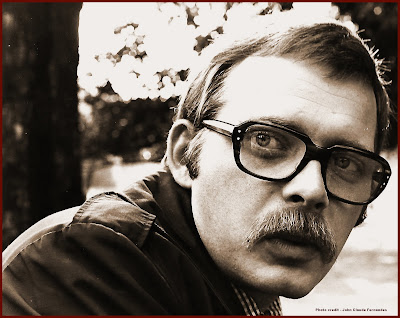

|

| My first specs |

With my new glasses, it was much easier for me to concentrate and I

proved an often pleasant surprise for Mrs. G who’d had half a mind to give up

on me in fourth grade. But still, our relationship was patchy and erratic and

varied between my sucking up by taking the initiative to clean the board and

pound the chalk out of the erasers out on the fire escape, to being pissed off

at her for her indifference, her euphoric favoritism for “the smart kids” or

her open and public criticism of some of the stupider things I did or said.

I was pleasantly surprised, however, when, at the end of the year (in

which I maintained a B- average) she wrote a note to my parents on the back of my

final report card in which she said that over the course of the two school years

that she had been my teacher, she had come to love me. She worried that I was

often distracted and indolent, but that she had seen great improvement in me

during the sixth grade. (Yes! I could see

now). She thought, furthermore, that I demonstrated great communications skills

and that she felt I was going to make a wonderful minister.

Oh, yes, I almost forgot. That was another distraction that plagued me

from the time I was about twelve until I was about fourteen—the thought that I

“had a calling”. This was something that led me to hold long conversations on

religious topics with our erudite pastor at the local Methodist church,

Reverend Fletcher Shoup. I even occasionally visited him at the parsonage,

where he had a cramped little den mostly taken up by theology-related books, a

few of which he lent me to read. I would also ambush my Uncle Don, who was a

Methodist pastor as well, whenever I got the chance, and would bend his ear

with my tortured self-doubt and fears regarding heaven and hell and the

salvation (or not) of my mortal soul.

Reverend Shoup, who was also my catechism teacher and the pastor who

confirmed me when I was thirteen, showed infinite patience. Uncle Don, not so

much. He was kind and helpful, but said I had a long time to think about these

weightier questions of both worlds, and maybe, for the time being, I should

just lighten up and enjoy being a teenager. His very human advice was the one

that won out.

In junior high, I pretty much passed for just another kid, albeit one of

only a handful of boys who excelled in band, art and English rather than in

football, basketball and track, but at least by then I was in the company of

other geeky outcasts and no longer cared...much. But it was there that while

keeping up in every other area, I fell further behind than ever in math.

This was due, in large measure, to the strange teaching philosophy of

Mr. V. Early on in the school year, Mr. V often took a sneering, sardonic look

around the room to see which students’ eyes were lighting up with understanding

of the problems he was chalking up on the board and whose had glazed over.

Finally, one day, after a pop quiz with broadly mixed results, he stood at the

front of the class, heaved a histrionically tired sigh and said, “Okay, from

now on, all of you who are getting this, come up and take your rightful places

at the front of the class. Those who don’t, you can just move to the back rows

and try not to bother the rest of us.”

I immediately stood, before the baffled gaze of some of my schoolmates,

and moved to the back of the class, half-expecting a covey of others to come

with me. They didn’t. I guess I was the only one who realized whom Mr. V was

talking to.

In high school, there were attempts (largely unsuccessful) to teach me algebra and geometry. In the first case, my teacher was Mr. G (no relation the Mrs. G). I immediately liked the man. I thought he was one of the funniest and bravest men I’d ever met. To have the neurological issues that he suffered and still want to stand up before a classroom full of bratty fifteen-year-olds was, to my mind, an act of very real valor.

Mr. G already had the look of a comedian to start with—a cockeyed clownish

face, which more often than not wore a quizzical smile, as if he’d just

recalled a private joke that he had no plan to let anyone else in on. But what

for silly, un-empathic teens was more comedic than tragic was the manifestation

of his uncontrollable neurological difficulties. He had an absolutely

incredible repertoire of tics and twitches that often overtook him several

times a class. On the first day he joked that he would issue towels to anyone

in the first row who thought they needed them. And, he added, we would soon

understand why.

Sure enough, partway through the first hour with him, in the midst of a

formula he was explaining as he wrote it on the board, Mr. G went rigid, one

arm down at his side, the other cocked, fist closed, as if about to throw a

hook. Then he began emitting a sort of glottal hum, rather like, I noted, the

strange grunted solfeging jazz great Erroll Garner did while he created magic

on the keys of his Steinway. And then he was stamping one foot while making a

rapid succession of spitting sounds through his tight lips, a dry surface

sound, like someone trying unsuccessfully to dislodge a bit of fuzz or a hair

from his lips. The fit ended as suddenly as it had begun, and Mr. G calmly and

unapologetically went on as if nothing had ever happened.

I really hated disappointing him. But after several months of watching

me struggle with the mysterious concept of unknown values, Mr. G, in comic

frustration, said, “Tell you what, Newland, there’s no reason for you to suffer

like this. I’ll just give you a coloring book and you can go enjoy yourself at

the back of the class. If you feel like participating, let me know.” I participated

enough to get a barely passing grade and still had geometry to look forward to

the next year.

If algebra had been challenging, geometry was next to impossible. My teacher, Mr. B, was a really professional and dedicated mathematician. I once heard him talk about a vacation to Europe that he and his wife long dreamed about. What deeply elated him when they finally went was seeing, up close and personal, all of the angles, arcs, vertices, columns, polygons and triangles—both equilateral and isosceles—that he had been able to note in the great architecture of the Old World. A somewhat portly, bald man with an impressive cranium to house his large brain, a pair of horn-rimmed glasses and an ever-present bowtie, he contrasted with Mr. G by being serious as a heart-attack. He sat at the back of the room with the roll book and, one at a time, called us by our full names to go to the board and chalk up whatever formula or figure he decided to ask us for. I lived in mortal fear of the words, “Dan Newland, go to the board, please.”

I tried to shrink as low as I could and, if possible, disappear, but

being called had nothing to do with capturing his attention or not. It was all

done from the roll book according to a meticulous plan. The relief of not being

called on one day was overshadowed by the feeling of impending doom that came

with knowing your name could well be called the next. You might have thought

that this constant fear of humiliation would have prompted me to study harder

and to seek tutoring help from one of my more mathematically inclined friends.

But you would be mistaken. By this time, I was completely immersed in my world

of music and literature and for me, nothing else existed. I was already working

after school and on Saturdays for a music store, giving private lessons to

numerous students and playing in nightclubs at least three nights a week. I was

additionally not only playing in our high school marching and concert bands,

but also in the All-Area Symphonic Band. Geometry? Who needed it? I just wished

I could opt out of it. But it formed a required part of the college prep

curriculum, and if I wanted to be a high school band director, as I told myself

I did, I was going to have to go to college.

Fortunately, Mr. B, the geometry teacher, maintained a sort of odd-couple

friendship with Mr. B the band director, for whom I was a star student and one

of his particular pets. It seems that my name came up in a conversation between

the two of them over lunch one day and when the first Mr. B told the second Mr.

B how disastrous my performance in geometry was, the second Mr. B asked the

first to, for godsake, go easy on me, because if I flunked geometry, I would

never get into music school.

Ever witheringly frank, the mathematical Mr. B called me aside one day during the last quarter of the school year and told me that the musical Mr. B had specifically asked him to cut me a break. He said that, in deference to his friend and colleague, he would be grading me “on the curve”—he didn’t specify plane curve or smooth curve and I was in no position to get into a discussion of differentiable geometry—in order to give me a pass even though I deserved to fail. “I don’t want to be the one to deny you a career in music,” he said, “and it’s not something you’ll ever need geometry for, no matter how important the subject may be to me.” I was overwhelmed with relief and gratitude.

|

| Percussion instructor |

But then, during the third quarter of my first and only year in the Ohio

State College of Education, School of Music, my doubts, once again entered

crisis mode. What in the hell was I doing studying to be a high school band

director when what I loved most about music was performing it. And I was also

leaning ever more toward being, first and foremost, a writer. I spent long

hours when I should have been cramming harmony and theory, which was my

academic nemesis, sitting in a quiet diner just off campus writing short

stories and a first novel that I had recently begun. I was doing quite well in

most of my music studies but as a percussionist, didn’t have a nearly strong

enough background in piano to pick up immediately on even the basics of

composing for anything more than a drum corps.

What I should really be doing, I told myself, was going to the Berklee

Jazz Conservatory in Boston. But who could afford it? In a quandary, I finally

decided to drop out and travel awhile. I made the decision after a face-off

with Harmony and Theory.

There was to be a major test, and I was about as lost as I could get.

The day before the test I spent writing instead of studying, then at night,

panicked and could think of nothing better to do that go drinking all night.

But my responsible side showered, changed and arrived for the test at 8 a.m. I

was still so drunk that it was hard to sit in my seat without falling out and

when I dozed off twice, pencil still to paper, in the first fifteen minutes,

Professor X, himself a jazz man, came over and put his hand my shoulder and

motioned me to follow. I lurched out of the room with him and in the hallway,

keeping his voice low he said, “Newland, geezus, man! You’re wiped out! Tell

you what. Go back to your dorm, get some rest, get your shit together over this

next weekend and next Monday at two, I’ll let you do the test in my office. How

does that sound?”

I agreed and thanked him profusely. And the following Monday, I went to

his office, took the test and passed. But I’d already decided that this band

director thing that everyone but I expected me to do was at an end.

|

| Reporter and student, Buenos Aires, 1976 |

But just before the start of my senior year, I was promoted to general

news editor in the newspaper where I was working and I no longer had time to

finish my degree, since I was only sleeping five hours a night as it was. A

couple of years later, the dean of the College of Law Translation School

approached me with an offer—finish my final year, get my degree, and immediately

start teaching translation at the school. I was honored, but for once in my

life, I knew exactly what I wanted to do, and I was already doing it.

Once not long ago, when talking to Darla over coffee and cake—we both

love coffee and cake—I commented that she had made it look so easy, school I

mean. She said, “Really?! Because it

wasn’t. I had to work my butt off.”

“Wow!” I said. “Because you made it look like it all came natural to

you.”

I said that if I’d had it to do over again, I would have chosen to be a

lot better. Educational excellence, I had learned, was a shortcut to any

intellectual endeavor. What I meant by that was that everything you learned

through formal education gave you a leg up because you were handed other

knowledgeable people’s know-how on a platter and were given savvy guides

(professors) to lead you to that knowledge. When you didn’t have it, it was still

possible to reach the same goals, but the road to them was full of doubt and of

trial and error. I said that I would have been more applied intellectually. A

stellar music student, a thorough and orderly student of literature, owner of a

master’s degree, less self-taught, better prepared, a well-formed intellectual.

Less of a workhorse. More of an individual who knew he had a message and how to

get it out. Perchance a bestseller.

She looked at me impatiently—as only big sisters can—and said, “Well,

you haven’t seemed to need it. You seem to have done just fine.” Maybe, she

said, if I had put all of my energy into being a stellar student, I never would

have done “all the amazing things you’ve done.”

She meant, of course, selling my car and traveling to South America for the first time when I was still in my teens. Dropping out of college the first time and spending three years traveling the States and Europe with the Army. Traveling to South America for a second and third times and the last time, landing a job as a reporter and sub-editor for a big-city newspaper. Using my GI Bill to return to college in a foreign land and in a foreign language. Working as a foreign correspondent for publications in the States and Britain that I had long admired. Reporting for one of the three biggest radio networks in the US. Becoming the managing editor of a newspaper. Being appointed by the US ambassador—under the administration of Ronald Reagan no less!—to the academic board of the Fulbright Scholarship Commission (perhaps the only non-college grad to ever hold that post). Being a player, if a small one, in several landmark chapters of world history. Earning my living for more than four decades as a writer and translator. Putting food on the table and clothes on my back with the written word throughout that time and never working at anything else—something precious few writers can say.

|

| Editor, Buenos Aires Herald, 1986 |

I knew I was fortunate. I knew I had nothing to complain about, that

despite some ups and downs and a few very rough patches, I’d lived a charmed

life. But ingrate that I am—always wanting more, always demanding that my most

delusional dreams come true—I forked up the last of the cake crumbs on my plate,

took a sip of coffee, and said, “Yeah, but it would have been nice just once in

my life to feel like I wasn’t walking the high wire. Just once to feel, “I’ve got this,” and not have that feeling

that, ‘Hey, I got ‘em fooled so far, but if they ever find out what an idiot I

actually am, I’m fucking toast!’ You know?”

“Of course I know!” she said. “Welcome to the club!”

Her answer took me completely by surprise. I had never thought that,

brilliant intellectual that she was, my sister might ever have had a moment of

professional angst anything at all like my own, and I think for a few seconds

she left me sitting there with my mouth hanging open.

Then I said, “More cake? More coffee?”

3 comments:

I loved it!!!

I love reading your "stuff"! There are so many moments of recognition here! "They all look so normal and put together. What's wrong with me?" "I'm doing the best I can with who and what I am in the only way I see possible to go at this moment in time." Fake it until you make it! Imposter syndrome! Your last few sentences nicely summed up the human condition. It is not just me, it is every one of us! It takes decades of living to learn that lesson.

Thank you so much, Jane! So glad to find a kindred spirit.

Post a Comment