I might have neglected to mention when I wrote about my New Year

resolutions last time https://southernyankeewriter.blogspot.com/2020/01/new-year-resolutions.html that as part of my self-improvement goals, I’m not

only determined to lose at least twenty pounds but also to get back into

training. I was already doing this to a certain extent by alternating treadmill

training with my usual walks in the mountains. The idea was to recover the

respiration capacity I’d lost as a result of a life-threatening lung injury

that I suffered a year and a half ago.

At first—a lot like when I first started blogging—I thought nothing much

would come of it and that, at this juncture, I’d have to settle for “as good as

it gets”. But to my surprise, the additional intensive training on the

treadmill started working wonders, and the recovery of lung capacity was really

noteworthy when I hiked up long steady hills, which, ever since the accident,

had become my bane. (I was kind of beginning to think I was going to have to

move from the mountains to the plains if I didn’t want to keep gasping for air

like a fish out of water every time I had to face the tiniest hillock).

Well, so while I was doing this aerobic program, which I had started in

physical therapy following the injury, I had to do my treadmill routine amidst

my old weights that had been collecting dust for the past two years. I should

note that weight-training has played an important role in my life off and on

since I was in my mid-twenties. In fact, at one time and in one Buenos Aires

gym or another—from the sleaziest (but best) facilities frequented by boxers,

wrestlers, cops, fire-fighters and bodyguards, to some of the most dazzling

modern weight and aerobic gyms in the city—I went through long periods in which

I would regularly spend three or four hours a session, four times a week

building strength, resistance and muscle.

Well, so while I was doing this aerobic program, which I had started in

physical therapy following the injury, I had to do my treadmill routine amidst

my old weights that had been collecting dust for the past two years. I should

note that weight-training has played an important role in my life off and on

since I was in my mid-twenties. In fact, at one time and in one Buenos Aires

gym or another—from the sleaziest (but best) facilities frequented by boxers,

wrestlers, cops, fire-fighters and bodyguards, to some of the most dazzling

modern weight and aerobic gyms in the city—I went through long periods in which

I would regularly spend three or four hours a session, four times a week

building strength, resistance and muscle. |

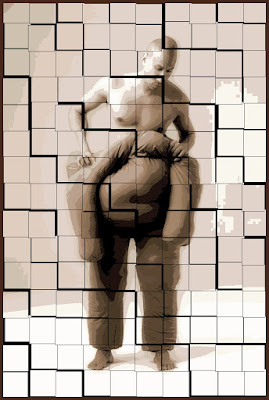

| Piñeyro in his prime |

I had the good fortune to do my earliest weight training in a rough,

down-at-heel gym where the clients were mostly guys who made a living with

their bodies and really knew what was what when it came to building muscle. I

was introduced to the place by my brother-in-law, Miguel, who had been an avid

body-builder since he was fifteen and had won several titles, including Mister Buenos Aires. He was (and still

is) close friends with the gym’s owner, Ernesto Piñeyro. I learned a lot in the

beginning from both of them. And muscle became a regular talking point whenever

Miguel and I got together.

Piñeyro had been a pro wrestler whose ring handle was “Mister Músculo”.

He was a favorite for spectators because he was so small and so perfectly built

and threw guys three times his size all over the canvas. But he was also a

serious contender in his weight class in international body-building

competitions, although he could never aspire to the top prizes because he was a

five-foot-seven miniature. He was so well-formed that, at a competition in

Miami, then-Mr. Universe, Arnold Schwarzenegger, asked Ernesto to pose with him

for part of a photo-shoot. Ever deadpan, laconic and witheringly frank, Piñeyro

thought about it for moment and then said, “Okay, but with you down on a knee

in the background and me standing in the foreground.”

His cheekiness tickled body-building star Schwarzenegger, and with a

hearty laugh, Arnold said, “Okay, whatever you say.”

Despite his tough-guy demeanor, Ernesto’s still waters ran deep and it

wasn’t until I’d known him for over a year that I learned that he not only had

a degree in physical education but also another one in fine arts.

|

| Bonavena and Ali |

But the guy who trained me the most was Omar Patiño. Omar had been Argentine

heavyweight champ Ringo Bonavena’s sparring partner. Boxing fans might recall

when, before the famous match between Ringo and Muhammad Ali, the American

champ had boasted, “He’s mine in nine.” But the hard-headed, flat-footed Bonavena

went the distance, fifteen rounds with the world champion, and it took Ali

three knockdowns in the last round to finally keep the two-hundred four-pound

Argentine down on the canvas for a ten-count.

But Patiño was a lot faster than Bonavena ever thought of being, two

hundred forty pounds of sheer muscle and no fat, a heavyweight who fought like

a bantam. In fact, his own trainer coming up had been the 1948 Argentine bantam-weight

champ, Cacho Paredes. Omar had also been chief bodyguard for several of the

country’s top Peronist union leaders and was, as Rocky Balboa’s fictional

trainer, Burgess Meredith, might say, “a very dangerous individual.”

Since I worked nights, I just happened to be in the gym at the same time

of the morning when Patiño was training. Since he knew and liked my

brother-in-law, and since we usually had the gym to ourselves at that hour, he

started taking an interest in me. “No, pal, you’re doing that wrong. Better

like this. It works the muscle deeper. Keep your back straight on the squats

unless you want a herniated disk. Try doing some rowing over here. You need

more strength in your shoulders. Don’t skimp on the crunches. Abs are your core

strength,” and so on.

I remember once when I was starting to feel pretty cocky and had loaded

up a couple hundred pounds on the vertical press and about midway through my

second set, I got a charley horse that stopped me cold. These weight machines,

most of which Piñeyro had built himself, had no safety features or fail-safes

and there was no way I was going to be able to get out from under without it

falling on me if I abandoned the maneuver with my legs still doubled.

I finally managed to grunt, “Omar...little help.” And in one swift, smooth

movement, he hefted the two hundred pounds of weight off of me with one hand

while grabbing me by the sweatshirt and dragging my own buck-ninety out from

under it with the other.

You gain a whole new kind of respect for a guy who can do that.

I think of him every time I start training again. And because of him,

whenever I do start again, I don’t have to go back and correct the movements.

He burned them into my brain from the outset and when you learn it from a guy

like him, you remember it.

Omar has had an important gym of his own in Buenos Aires for years now

and specializes in training and managing young fighters. Some of the best

Argentina has to offer.

But anyway, in the last ten years or so, despite having a fairly

complete home gym, I’ve done less and less, letting advancing age, overweight

and laziness lull me into apathy. Especially since the jobs required of living

where I live—gathering, sawing and chopping firewood, for instance—plus my

mountain and forest walks kept me in reasonably good shape. But the prolonged

recovery period following my injury and the miraculous recovery that I’d

undergone from cardiac arrhythmia the year before that, really took their toll.

And I could see and feel the reduction in my muscle mass and in my level of

physical resistance.

So, one thing kind of led to another, and I’m just timidly returning to

a light resistance training routine. Now, when I say light, I really mean

light. When I was at my peak in my late thirties, I was regularly benching two

hundred forty or two hundred fifty pounds and doing squats with three hundred.

That, as they say, was in another life.

In the last commercial gym I worked out in regularly, I learned a lot

about the benefits of high reps and low weights in what was called “the

circuit”. The circuit was made up of perhaps a dozen Nautilus-type and

universal weight machines on which the idea was to do three sets of fifteen

repetitions with only as much weight as you could comfortably do them and still

make it through the entire circuit. There was a green light for each set and a

red for each ten-second rest to help you budget your time. But in practice, it

was a mad race from one machine to the next.

|

| Circuit |

One circuit was about five hundred forty reps that worked your entire

body, and depending on the time I had to work out, I did between two and three

circuits. At first it was absolutely grueling. This is when weights become not

only resistance training, but also aerobic. And it’s not until you’ve done it

for a month or so that you start really hitting your stride. But once you do,

it’s exhilarating! Or at least it felt that way to me. And once I got so that

the circuit was a pleasant routine three or four times a week that I never

wanted to miss, I started alternating, one week circuit, another week heavy

lifting. Eventually, I also added jogging to the mix and felt so healthy it was

scary.

There came a time that I felt what well-trained athletes must feel. That

was something I knew nothing about, because, as a teen, I was a nerdy musician

bookworm, who thought anything connected with the world of sports was beneath

me. The only thing I did well was swim, but I wouldn’t have thought of having

any part of swimming as an organized sport. And as soon as I was lying on my

towel drying off, the first thing I did was light up a smoke. But now, with

this intensive weight-training, I understood that look of physical and mental

confidence of the athletes I’d known in school. I felt like I could walk through

walls and pick my teeth with the splinters. Even after Army combat training I

had never been in this kind of shape, since, by this time, I had pretty much

kicked my heavy smoking habit, which had followed me all through my Army days

from my early teens. Suddenly, I felt physically confident and competent for

the first time in my life.

I remember at the time that I was at a peak in that transformation, I

was running the news desk in a newspaper in Buenos Aires. My cables editor was

a retired sergeant major from the Argentine Army. It was the time of the

so-called “dirty war” following a military coup that placed the Armed Forces in

bloody charge of the country, and military and ex-military men did concealed-carry

as a matter of course. They also displayed the arrogance of an unquestioned

ruling class.

This aging ex-NCO was notorious for doing things like flashing his weapon

to quickly end traffic disputes with other drivers or any other time that he

felt the least bit threatened. When he came to work, he would walk to his desk

across from mine on the news desk, open the top drawer, reach under his sport

coat to retrieve his nine millimeter service pistol from his belt and deposit

it inside his desk until time to go home.

So one night, I arrive carrying my briefcase in one hand and my gym bag

in the other and as I’m taking off my blazer, rolling up my sleeves and getting

ready to settle in for the night’s work, I see him watching me with a crooked,

sardonic grin on his face.

“What?” I say.

“You’re getting big.”

“Am I?”

“Yes. I remember what a tall skinny kid you were when you first came

here.”

“I was twenty-four and had been three years in the Army. Hardly a kid.”

He went back to cutting and separating cables and I got down to editing

copy.

Then he looks at me again and says, “Now tell me this...”

“What?”

“Why do you do it?”

“What?”

“All this body-building.”

I put down my ballpoint pen and looked at him. “To feel healthy,” I

said. “To get strong.”

He grinned that crooked, sarcastic grin again, and sliced a few more

cables from the teletype roll. Then he stopped, laid down his ruler, and opened

his desk drawer.

“Because, you know what?” he said.

“No, what?” I said, getting

annoyed at the interruptions.

With that, he pulled the nine millimeter out of its hiding place, held

it up for me to see, and said, “No matter how strong you get, I put a couple of

pieces of lead in you, and you don’t get back up. And it won’t matter how

strong or weak I am.”

“Yeah, that’s true,” I said, “but I’m getting pretty quick. And if I can

get across this desk before you can chamber a round, aim and fire, I’ll snatch

your heart right out of your chest and run the pistol so far up your ass that

they’ll have to remove it surgically.”

He nodded, chuckled a wry chuckle to himself and put the pistol back in

his desk. And that was the last time he ever flashed a piece in the newsroom

again.

So anyway, as I was saying, what I’m doing now, at seventy, is mere

recovery. Trying not to be so decrepit. But I have to admit that I tend to stop

and read when I see stories about old men who have either begun or returned to

weight training in their senior years and gotten into incredible shape again.

Will I be one of them? Will I have the constancy and the willpower and the

mental and emotional stability and discipline that it takes? I admit, it’s hard

for me to imagine I will. But, as the great Yogi Berra said, “It ain’t over

till it’s over,” and just trying to get going again will be better than not

trying at all.